The low-intensive and high-potential agriculture sector should be the country’s best bet to recover from the economic losses caused by the coronavirus and subsequent lockdowns.

In his recent nationally televised speech, Prime Minister Narendra Modi openly thanked the Indian farmer and the taxpayer in the same breath. The farmers though wear both hats as they pay taxes on most of their inputs. With no set off opportunity as agri-produce sales are zero rated, there is no input credit, so perhaps the farmer was appreciated twice, as a provider of food and taxes.

The PM announced that he would extend the PM Garib Kalyan Aan Yojana, the free food grain and pulses support scheme for another 5 months to 800 million Indians. It is not clear if he included the farmers who grow these crops because they keep their own grains and only sell a marketing surplus. If he hasn’t, then the math doesn’t add up. But that is not the point. This gesture could be made because the country’s granaries are full. So the farmer was thanked for growing the crops, and the taxpayers for paying for the subsidy, which again, because of GST, ironically, includes the beneficiaries too. But, all in all, it is a creditable situation, especially because of the collapse of urban India in the same period, that rural India harvested a bumper Rabi or winter crop, 150 million tons in 2020 compared to the 139 million tons in 2019.

During the nationwide lockdown, urban and industrial India were almost frozen. Though the unlock procedure has begun, this economy is only sputtering back to life. Different states have also imposed differing restrictions. However, in a rare case of unanimity, the one sector that was set free early on in the lockdown was agriculture, across the country. Not out of any sense of altruism or concern, but simply because it was time for the Rabi harvest. Farmers were not going to let their standing crops be subject to lockdown rules and bear the loss. Better sense prevailed and very early in the lockdown, agriculture operations were allowed.

The result was that the country recorded a bumper harvest of a range of different agri-produce. Reports of rakes of wheat being despatched from Punjab to far away Assam were received. Fortunately for the railways, the movement of the rabi harvest and food grains enabled income, given that passenger and industrial goods services were closed for most of the lockdown period. The railways recorded over a 50% increase in income and almost a 100% increase in volumes of grains moved, in April and May this year. No small achievement during a period of total shut down. Again, it was thanks to the Indian farmer that this could happen.

The bountiful harvest has converted into an uptick of demand by rural India. These include tractors, two-wheelers, agricultural inputs and of course demand for consumer goods to the extent that lockdown rules permit supply and sales. Now, with a normal monsoon predicted and which has covered India two weeks ahead of schedule, the Kharif crop operations are on in full swing. It is likely that the country will also have a bountiful monsoon harvest, following a record Rabi, so an additional source of income for the farmers, as many do both seasons. Two bumper harvests in one financial year when all else has stuttered to a stop or is sputtering to restart is a big boost to the country and the economy. It also needs to be appreciated that the millions of migrants have been absorbed back by the rural areas after they were unfortunately abandoned in urban India. So not only did the farmer feed urban India, and herself, she also fed and sheltered the returning migrant family member.

The agriculture ordinances

In this period, with little coverage or discussions, the government has promulgated three ordinances on agriculture. This is being touted as the ‘1991’ moment for Indian agriculture. In a nutshell, these are, the Essential Goods Act being given the go by, allowing unfettered sales and national movement of all agri-produce, direct sales being allowed by a farmer outside the APMC, or trader controlled mandis and, contract farming. These initiatives seek to unshackle the Indian farmer.

Additional support has been given by the extension of the ‘TOP to TOTAL’ scheme where transport and storage subsidy of 50% has been given for a wide range of crops, for a period of six months. All for the good, if only, the mandarins, a politically inappropriate term in these times, in the policy and rule-making roles, would let the Prometheus that is Indian farming be unbound. Unfortunately, as the leopard doesn’t change its spots and become a tiger, the mandarin too will stay one. So impractical rules like procuring a minimum of 100 MT and the minimum distance between the centre of production and consumption should be 100 km for availing the benefits of the scheme immediately removes the hundreds of millions of small farmers who sell in their immediate vicinity and produce in low double digits measured in tons.

Similarly, our inability to think big, and the hangover of a Gandhian socialist outlook, thinks of food processing as tiny industries making papad and pickles run by women self help groups in village clusters. There is no thought as to how supply chains for packaging, processing and selling would work or global quality be produced. Loans have been announced for such ventures, which have a small chance of success.

Equally limiting is the thinking of district wise export crops. Classical Soviet-era thinking which is buried in the hubris of market economics and India’s farming diversity at the individual farmer level.

Last year, the agriculture industry produced a billion tons of agri-produce, which includes 292 million tons of food grains, 340 million tons of fruits and vegetables. The sector spans 127 agro-climatic zones and the country has 200 million hectares of arable land, apart from a 7500 km-long coast line. The sector is a potential global leader.

A very timid goal

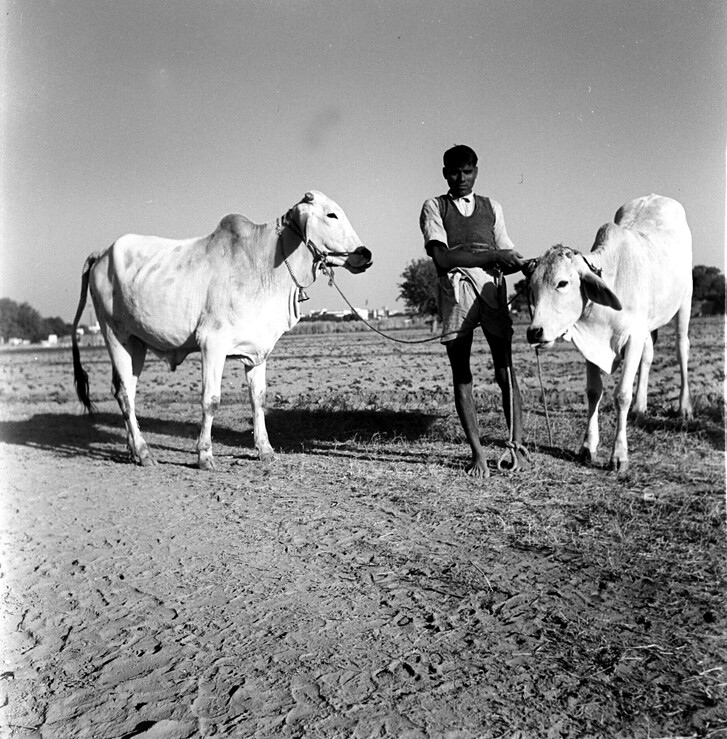

India has set a very timid goal for agri-exports, from around $35 billion to $60 billion in the next three years. A mango tree or a cow matures in around ten years for optimum yield. So these kinds of targets are self-limiting. The global trade in fruits and vegetables alone is over $200 billion today, set to double in the next five years. Global trade of all agri-produce including marine and forestry products, is in the region of $2 trillion the size of the Indian economy today. India should set a target of 1 trillion dollars of agri-exports, including marine and forestry in the next ten years, including using it as soft power to feed countries which have a food security challenges.

Together, the EU and the US export around $350 billion today (Europe around $210 billion and the US, $140 billion) compared to our $35 billion. Our potential is a lot more than both. We need to negotiate an equitable trade regime and a reduction of duties for Indian value-added exports to become a significant player in the global value chains.

The focus on agriculture will also enable a better distribution of income. Given the hundreds of millions involved in agriculture and allied industries and its multiplier effects, the impact will be well distributed, both at the level of the small farmer and spatially across the country. This will prevent concentration of wealth, as has happened by the urban and industrial focus of the last 20 years. With the top 1% of Indians currently owning four times the wealth of the 70% of the poorest, the next phase can’t be a repeat, without having some significant and unpleasant social consequences.

Unleashing Indian agriculture can create a storm of opportunities. From drones to AI, digital devices, consumption of broadband, light engineering, storage infrastructure, logistics, agri-equipment to name a few, the sector can utilise many recent technological developments. The small Indian farmer, on the back of a high tech-enabled, globally-connected environment can show the way forward.

The upstream and downstream multiplier effects are also significant. Upstream will lead to a demand of farming machinery, fertilisers, agro-chemicals, inputs like seeds, micro-irrigation systems and protected cultivation equipment. These in turn upstream into metals, petroleum-based chemicals, engineering components like motors, pumps, pipes and more. Solar pumps and drip irrigation systems can become items of large volume business.

Downstream, there can be a significant jump in infrastructure, static and mobile cold chain equipment, food processing and allied industries, a significant demand for food processing equipment, all of which are also employment-intensive and MSME driven, and of course in retail services including e-commerce as seen during the lockdown period.

A relevant factor of this sector is its low capital intensity. In comparison, to produce approximately 110 million tons of steel, the industry has borrowed over Rs 300,000 crore, of which nearly half is classified as stressed assets. To produce over a billion tons of agri-produce, the borrowings of the agriculture and allied industries are around Rs 9 lakh crore, which rolls annually, with the crop cycles. The employment intensity per rupee of borrowing, measured by thousands employed per Rs 1000 crores borrowed, tells a story: seven in steel vs 700 in agriculture and allied industries. The steel industry estimates of direct and indirect employment is 2 million. For agriculture and allied industries, it is 700 million. For a country that needs to employ hundreds of millions with a limited ability to provide capital, it is clear where our focus should be.

Source: https://bit.ly/3034kDK