The PM suggested these reforms at a high-level review meeting on the agricultural sector, which was also attended by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, home minister Amit Shah, agriculture minister Narendra Singh Tomar, and senior officials.

Outlining an ambitious post-pandemic agenda for agricultural reform, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Saturday asked his top ministers and bureaucrats to start working on a new set of reforms to cut down on archaic regulations, raise farm-gate prices, unify domestic markets as well as integrate the farm economy into global value chains.

These have been demands by key farmer groups as well as a range of economists and agricultural experts over the years.

The PM suggested these reforms at a high level review meeting on the agricultural sector, which was also attended by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, home minster Amit Shah, agriculture minister Narendra Singh Tomar and senior officials. The meeting was in a series of reviews the PM is undertaking on key sectors, in the backdrop of the national lockdown which has adversely affected the economy.

The PM sought further reforms in agricultural marketing, which is a reference to the mandi system that controls buying and selling of farm produce, among other issues. He said he was not averse to bringing “appropriate” new laws or changing old ones to firmly integrate farm markets across the country so that cultivators and traders can transact without restrictions. “Essentially, he wanted one nation, one market,” said a top official familiar with the deliberations of the meeting.

The PM also held a “general discussion” on genetically modified crops, a tricky subject given the widespread opposition to transgenics in the country. “It was a discussion that evaluated the various advantages and disadvantages of transgenics. The PM wanted updates on options to raise productivity, while lowering farming costs,” said the official quoted above. The PM stressed last-mile dissemination of technologies developed by agricultural research bodies.

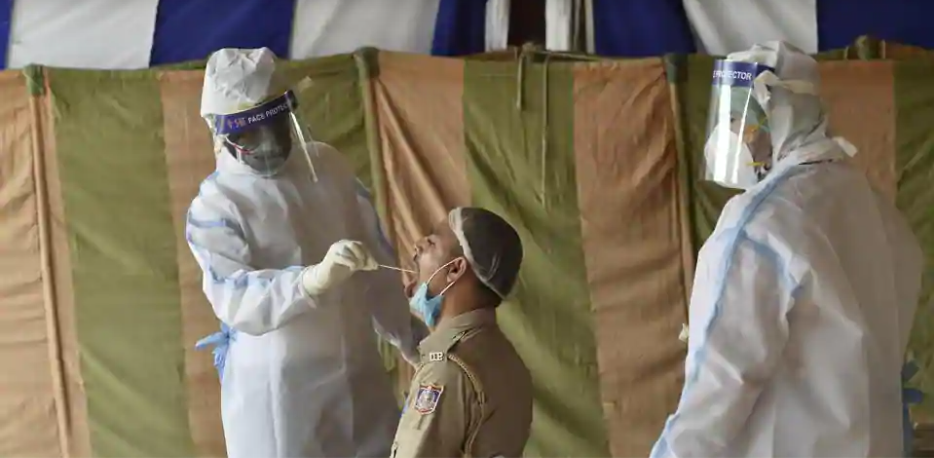

The Covid pandemic has pressured farm incomes, upending the farm-to-fork supply chain, despite full exemptions to the farm sector. A nationwide curfew caught farmers by surprise on March 24. During its the initial days, labour shortage and empty wholesale markets led farmers to dump new harvest, especially perishables.

Although agriculture accounts for 16.5% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP), nearly half the population in the country depends on a farm-based income, underscoring the sector’s importance for livelihoods.

The big focus on Saturday was on new ideas to intervene in the agriculture marketing system so as to make them freer, a second official said. Despite several model laws at the federal level — which serve as guidance for states — trade in agricultural commodities remains fettered by state-specific legislations, which prevent farmers from freely accessing food markets.

The discussions are a nod to a renewed farm agenda, which may, in all likelihood, see fresh legislations being moved in Parliament. “The honourable prime minister wants integrated markets. One state should be agreeable with another state as far as agricultural policies go,” the second official said.

The Indian agricultural market is fragmented. Each state has distinct regulations. Restrictions on where farmers can sell and to whom, as mandated by the Agricultural Produce Market Committee Acts, in various states, continue to thwart farm trade.

The second official said a new legal framework governing investment and technology in agrarian economy could be necessary and the “PM acknowledged that”.

“The focus was on making strategic interventions in the existing marketing ecosystem and bringing appropriate reforms in the context of rapid agricultural development,” an official statement said.

K. Mani, an economist with the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, said the first step for these ideas to be successful was to have an interstate council such as the one for the Goods and Services Tax.

Under a decades-old system, each state has scores of tight market zones to serve as exclusive buyer-seller platforms for an area. This system of ‘mandis’ or markets is both a physical and at times fiscal barrier, preventing seamless transactions of goods.

The second official cited above said the prime minister wanted a massive scaling up of a federal e-commerce platform for farmers and traders, known as the Electronic National Agricultural Markets or the e-NAM app. The PM’s push for the app came in the backdrop of agriculture minister Tomar saying, separately, that more than 166000 registered farmers across the country are now selling their produce by transacting from home and praticising social distancing, with nearly half of the country’s 1500 major farm-end commodity markets now going online. This is the first time wholesale food markets in large states, such as Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka, have joined the digital supply chain.

Farmers on the e-NAM app can strike deals for their harvests remotely by first uploading pictures of their samples and then getting these samples scientifically checked for quality by remote assayers, without having to move entire truck loads to physical markets. The e-NAM platform now has a total of 785 markets online.

Saturday’s review was preceded by recommendations earlier this year from a committee of secretaries tasked with reviewing the agriculture sector. It identified persistent trade barriers within the mandi system that continue to hurt producers.

The government could consider a “single mandi tax for the country” and “removal of levies” charged to traders and farmers when farm goods are sold from one state to another, known as interstate mandi tax, a third official said.

“Making farm marketing reforms work is similar to opening FDI in manufacturing. That’s how big it is. It’s after all about prices for producers,” said S Mahendra Dev, director and vice-chancellor of the Mumbai-based Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research. Dev formerly headed the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, the federal body that fixes minimum support prices.

Ushered in during the 1960s, most Agricultural Produce Market Committee Acts – each state has its own law — require farmers to only sell to licensed middlemen in notified markets, usually in the same area as the farmer, rather than directly to buyers elsewhere. These rules were meant to protect farmers from being forced into distress selling. But over time, they have spawned layers of intermediaries, spanning the farm-to-fork supply chain. This results in a large “price spread” or the fragmentation of profit shares due to the presence of many middlemen.

Saturday’s meet also discussed possible model land tenancy laws. Outdated land tenancy laws in many states mean that tenant farmers don’t get access to farm loans because they don’t own land. Tenancy reforms can lead to more contract and organised farming without affecting “adverse possession” or ownership of land.

“One reason why agriculture has suffered is that we have not liberated the sector as we have done for the industry. Without compromising food security, you have to open up. The government cannot assume it knows everything. I think that’s what the government has realized now,” said Manoj Kumar Panda, the RBI chair professor at the Institute of Economic Growth, University of Delhi.

Bureaucrats suggested the creation of commodity-specific administrative bodies and the promotion of agriculture clusters as well as contract farming to boost exports.

Source: Hindustantimes

Link:https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/govt-plans-major-agri-reforms-post-corona/story-EISmhgFEzDaI4386TorfwM.html