Agriculture remains the primary sector of the Indian economy. While it accounts for merely 16 percent of the country’s GDP, approximately 43.9 percent of the population depends on it for their livelihood. In recent years, indebtedness, crop failures, non-remunerative prices and poor returns have led to agrarian distress in many parts of the country. The government has come up with various mechanisms to address these issues: insurance, direct transfers and loan waivers, among them. However, these mechanisms are ad hoc, poorly implemented and hobbled by political dissension. In February 2016 the government launched the crop insurance scheme, Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) to reverse the risk-averse nature of farmers. While the PMFBY has improved upon its predecessors, it faces structural, logistical and financial obstacles. This paper makes an assessment of the performance of the PMFBY in terms of adaptability and the achievement of the objective of “one nation, one scheme.”

Attribution: Ruchbah Rai, “Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana: An Assessment of India’s Crop Insurance Scheme”, ORF Issue Brief No. 296, May 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

India’s agricultural sector, which contributed 16 percent[1] of the country’s GDP in 2017, supports the livelihoods of 43.9 percent of the population.[2] Employment in this sector has decreased by 10 percentage points within a decade, from 53.1 percent in 2008 to 43.9 percent in 2018.[3] The sector is facing manifold problems such as crop failures, non-remunerative prices for crops, and poor returns on yield. Agrarian distress is so severe, that it is pushing many farmers to despair; about 39 percent of the cases of farmer suicides in 2015 were attributed to bankruptcy and indebtedness.[4]

While the Government of India (GoI) has made various efforts to address farmers’ grievances, the policies are insufficient, weighed down by their being merely ad hoc and subject to political wrangling. There is an imperative for a financial safety net that does not consist only of direct transfers and loan waivers—short-term solutions that often prove to be counterproductive—but a framework that is timely, consistent and improves agricultural productivity and, in turn, farmers’ quality of life.

Farmers are vulnerable to agricultural risks and thus need an insurance system. While India has had one since 1972, the system is rife with problems, such as lack of transparency, high premiums, and non-payment or delayed payment of claims. India’s first crop insurance scheme was based on the “individual farm approach,” which was later dissolved for being unsustainable. The next insurance scheme was then based on the “homogeneous area approach.” In 1985, the Comprehensive Crop Insurance Scheme was implemented for 15 years; improvements were made based on the area approach linked with short-term crop credit. Its successor, the National Agricultural Insurance Scheme, was implemented to increase the coverage of farmers, both those with existing loans and those without. However, despite the modifications, the scheme failed to cover all farmers, and in Kharif season 2016, the GoI formulated the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) to weed out the issues in the previous crop insurance schemes.

The PMFBY is a crop insurance scheme that improved upon its predecessors to provide national insurance and financial support to farmers in the event of crop failure: to stabilise income, ensure the flow of credit and encourage farmers to innovate and use modern agricultural practices. However, a close assessment of the scheme and its implementation shows that the PMFBY is afflicted by the same problems as the previous schemes. This brief attempts to assess the performance of the PMFBY. It offers recommendations to make the PMFBY a sustainable mechanism that will protect farmer incomes and reverse their risk-averse nature.

The Rationale for Crop Insurance

Indian agriculture has been progressively acquiring a ‘small farm’ character. The total number of operational holdings in the country increased from 138 million in 2010–11 to 146 million in 2015–16, i.e. an increase of 5.33 percent.[5] Small and marginal farmers with less than two hectares of land account for 86.2 percent of all farmers in India but own only 47.3 percent of the crop area.[6] Semi-medium and medium landholding farmers who own two to 10 hectares of land, account for 13.2 percent but own 43.6 percent of the crop area, which supports the claim that the average landholding size has declined from 1.15 hectares in 2010–11 to 1.08 hectares in 2015–16.[7] To be sure, a small landholding is not automatically a deterrent to productive farming. In China, for example, despite a small average land size of 0.6 hectare, farmers have achieved higher productivity due to efficient practices involving mechanisation and R&D, in turn leading to increased surpluses.[8] In India, such small average holdings do not allow for surpluses that can financially sustain families. India’s primary failure has been its inability to capitalise on technology and efficient agricultural practices, which can ensure surpluses despite small landholdings.

India’s farmers need insurance for another reason: the commercialisation of agriculture leads to an increase in credit needs, but most small and marginal farmers cannot avail credit from formal institutions due to the massive defaulting caused by repeated crop failure. Moneylenders, too, are apprehensive of loaning money, given the poor financial situation of most farmers.[9] According to the All India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS) 2013–14,[10] indebtedness is more widespread amongst cultivator households than their non-cultivator counterparts. In 2014, 46 percent of the cultivator households were indebted, with an average amount of INR 70,580 in debt.[11] Institutional agencies (commercial banks, regional rural banks or insurance companies) held 64 percent of agricultural debt in 2013, while non-institutional agencies (moneylenders, family or friends) held the remaining 36 percent.[12] Professional moneylenders held the maximum share of agricultural debt (29.6 percent),[13] indicating that rural households still depend on them for easy credit. The AIDIS[14] 2013-14, also stated that non-institutional agencies advanced credit to 19 percent of the rural households and institutional agencies to 17 percent. This creates indebtedness amongst the farmers, leaving them disadvantaged to avail credit for further production. Farmers prefer informal loans as they are easier to obtain; however, they come with exorbitant interest rates. The lack of sufficient access to institutional capital for non-farm expenditure further drives farmers to meet these expenditures using credit from non-institutional sources. Additionally, those who lease land face more risk than those who own land, because certain regulations categorise farmers who have land on lease as “landless.” Not owning land thus makes it difficult for farmers to get loans from banks, making informal credit institutions more lucrative.

A third reason is related to climate change: higher incidence of extreme weather events aggravates agrarian distress. Floods and droughts leave farmers in a period of flux. A lack of preparedness makes them vulnerable to harvest losses, especially given the money already paid for capital, e.g. seeds and fertilisers. This results in fluctuating incomes and unstable livelihoods. Around 52 percent of India’s total land under agriculture is still unirrigated, posing problems for farmers investing in production and cultivation.[15] According to the Economic Survey 2017–18,[16] extreme temperature shocks result in a four-percent decline in agricultural yields during the Kharif season and a 4.7-percent decline during the Rabi season. Similarly, extreme rainfall shocks—when the rain is below average—lead to a 12.8-percent decline in Kharif yields and a smaller but not insignificant decline of 6.7 percent in Rabi yields. The agricultural productivity patterns as a result of climate change can reduce annual agricultural incomes between 15 percent and 18 percent on average, and between 20 percent and 25 percent for unirrigated areas.[17]

The three factors discussed above, along with lackadaisical implementation of agricultural policies, render farmers highly vulnerable. Crop insurance schemes were formulated to tackle such issues that hinder the productivity of the agricultural sector and to reduce their negative financial impact on farmers. Such schemes attempt to not only stabilise farm income but also create investment, which can help initiate production after a bad agricultural year. The GoI has been updating its crop insurance schemes to keep up with the changing times. The most recent one was launched in 2016, a scheme that rectifies past errors and ensures increased farmer participation, which in turn promises increased agricultural productivity and a bigger share for agriculture in GDP.

Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY): An Overview

The PMFBY has made several improvements compared to its predecessors, the National Agricultural Insurance Scheme and the Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme. One of the highlights of the PMFBY is the absence of any upper limit on government subsidy, even if the balance premium is 90 percent. The scheme was implemented in February 2016 and was allocated an initial central-government budget of INR 5,500 crore for 2016–17.[18] It has increased by 154 percent, as announced in the Interim Budget of 2019.[19] This massive increase in the outlay for the scheme shows that it is important for the government to insure all farmers and guarantee financial support and flow of credit to them in the event of crop-yield loss.

Features of the PMFBY[20]

- Coverage of Farmers: The scheme covers loanee farmers (those who have taken a loan), non-loanee farmers (on a voluntary basis), tenant farmers, and sharecroppers.

- Coverage of Crops: Every state has notified crops (major crops) for the Rabi and Kharif seasons. The premium rates differ across seasons.

- Premium Rates: The PMFBY fixes a uniform premium of two percent of the sum insured, to be paid by farmers for all Kharif crops, 1.5 percent of the sum insured for all Rabi crops, and five percent of sum insured for annual commercial and horticultural crops or actuarial rate, whichever is less, with no limit on government premium subsidy.

- Area-based Insurance Unit: The PMFBY operates on an area approach. Thus, all farmers in a particular area must pay the same premium and have the same claim payments. The area approach reduces the risk of moral hazard and adverse selection.

- Coverage of Risks: It aims to prevent sowing/planting risks, loss to standing crop, post-harvest losses and localised calamities. The sum insured is equal to the cost of cultivation per hectare, multiplied by the area of the notified crop proposed by the farmer for insurance.

- Innovative Technology Use: It recommends the use of technology in agriculture. For example, using drones to reduce the use of crop cutting experiments (CCEs), which are traditionally used to estimate crop loss; and using mobile phones to reduce delays in claim settlements by uploading crop-cutting data on apps/online.

- Cluster Approach for Insurance Companies: It encourages L1 bidding amongst insurance companies before being allocated to a district to ensure fair competition. A functional insurance office will be established at the local level for grievance redressal, in addition to a crop insurance portal for all online administration processes.

The PMFBY was implemented to ensure transparency, availability of real-time data and an accurate assessment of yield loss.

The state-run Agriculture Insurance Company of India (AIC), which has been allocated the largest number of districts under the scheme, handles insurances in other districts and states. The others are the United India Insurance, New India Assurance and Oriental Insurance, and private general insurers such as HDFC ERGO, ICICI Lombard, Reliance GI and Iffco-Tokio.

Table 1: Comparison of crop insurance schemes in India

| Feature | NAIS (1999) | MNAIS (2010) | PMFBY (2016) |

| Premium rate | Low | High (9–15%) | Low (Govt. to contribute five times that of farmer) |

| One season-one premium | Yes | No | Yes |

| Insurance amount covered | Full | Capped | Full |

| On account payment | No | Yes | Yes |

| Localised risk coverage | No | Hailstorm, landslide | Hailstorm, landslide, inundation |

| Post-harvest losses coverage | No | Coastal areas | All India |

| Prevented sowing coverage | No | Yes | Yes |

| Use of technology | No | Intended | Mandatory |

| Awareness | No | No | Yes (target to double coverage to 50%) |

| Insurance companies | Only government | Govt and private companies | Govt and private companies |

Source: PIB, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, January 2016.

The models prior to PMFBY were claim-based insurance schemes. The NAIS was backed by a government-funded insurance company called “Agriculture Insurance Company,” which collected premiums from farmers without any subsidy and then used that money to pay the claims at the end of the season. On the other hand, the PMFBY allows a subsidy in the premium-based system, which is implemented through a multiagency framework of select private insurance companies, the ministries of agriculture, GoI and state governments in coordination with commercial banks, cooperatives, regional rural banks and regulatory bodies, e.g. the Panchayati Raj.[21] Thus, the premium is subsidised by the centre and state governments to reduce the burden on farmers.

The PMFBY was created to target 50 percent of all farmers, with the promise of compensation in case of crop loss. The previous schemes saw low enrolment rates due to a lack of trust. Moreover, under those schemes, the dissemination of agricultural insurance was low and stagnant in terms of the area insured and the farmers covered in the previous schemes due to high premiums, the lack of land records, low awareness and the absence of coverage for localised crop damage.

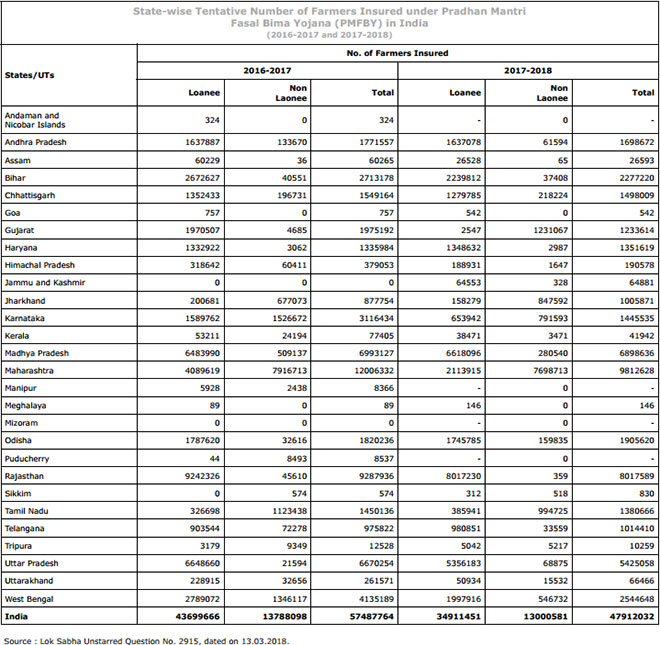

Since its implementation, the PMFBY has achieved 41-percent coverage of farmers—this may be considered impressive, particularly when compared to the 28-percent coverage of farmers achieved under the three previous schemes combined (WBCIS + NAIS + MNAIS).[22] During its first year, 58 million farmers were enrolled in the PMFBY, a quantum jump from the 30 million insured in the previous year under the MNAIS. However, there has been a fall in the number of total farmer applicants from 58 million in 2016–17 to 47 million in 2017–18.[23]

One could argue that the previous schemes were based on a better model, wherein the government created a fund that would collect premiums and then use it to pay off the remaining overhead claim settlements. However, this trust model was not resilient. Competition is necessary to bring down premium rates, and the government must step back after it has corrected the market failures. The private sector is required to pool in larger amounts of money, and with the help of the government, they can reach the masses through agricultural subsidies. Under the PMFBY scheme, the government can correct market failures before pulling back. In India, a private-public partnership works best in the agricultural sector, since the government is crucial in data collection and financial premium support in the form of subsidies, while the private sector enables the availability and mobility of credit.

Table 2 shows the percentage change of certain indicators to ascertain and compare the impact of the PMFBY on Kharif 2016 and Kharif 2017. Due to a lack of data on Rabi 2017–18 on the PMFBY website, the table does not show the percentage change during this season. However, there has been a significant increase in the number of claims paid and farmers benefitted: 64 percent and 29 percent, respectively.

While the positive effects are significant, it is important to also discuss the negative changes. As Table 2 shows, the number of insured farmers has declined by 14 percent from Kharif 2016 to Kharif 2017, and the total area insured has decreased by one percent over the span of one year. The PMFBY has therefore failed to achieve its main targets, i.e. increasing the area and the number of farmers insured.

Table 2: Percentage change in indicators for Kharif season under PMFBY

| Kharif 2016 | Kharif 2017 | Percentage Change | |

| Farmers insured | 40,258,737 | 34,776,055 | –0.14 |

| Claims paid (crore) | 10,496.3 | 17,209.9 | 0.64 |

| Gross premium (crore) | 16,317.8 | 19,767.6 | 0.21 |

| Area insured (ha) | 37,682,608 | 34,053,449 | –0.10 |

| Farmers benefitted | 10,725,511 | 13,793,975 | 0.29 |

Source: Author’s compilation using data from the PMFBY Website.

This failure is a result of some fundamental issues in the scheme, which must be discussed to create a more holistic crop-insurance scheme that mitigates risks for both farmers and food security.

An Assessment of PMFBY Performance

While the PMFBY aims to be a transformative scheme, its implementation has been poor, with various issues in its execution at the state/district level.

Structural Issues

- Since states choose to voluntarily implement the PMFBY, it is their responsibility to notify crops. However, it is unclear how states should choose the major crops during a season for different districts, which results in the exclusion from insurance coverage of farmers who grow non-notified crops. Further, state governments use their discretionary powers to decide how much land will be insured and the sum insured, to reduce their burden of subsidy premiums. Thus, farmers often find it pointless to buy the insurance if the sum insured is less than their cost of cultivation. During Kharif 2016, Rajasthan decided to minimise the landholding insured to save themselves INR 60 lakh.[24]

- An article in Down to Earth[25] noted that in a village in Sonipat, farmers were coerced to pay the premium amount with a condition that they would have to pay seven percent interest subsidy on a loan. This is unfair if the farmers have not received their claims, and it prevents small farmers from taking new loans. Vulnerable farmers under debt and in need of new loans are unable to avail this insurance unless all dues are paid, putting them in a vicious cycle of debt.

- Farmers are apprehensive about the scheme because of a trust deficit, which is a result of the mandatory credit-linked insurance. The premium is deducted from a farmer who has taken a loan from any banking institution without their consent and, sometimes, even without their knowledge. Loanee farmers do not have the choice to opt out of this scheme and find it unfair to pay the premium each season without being compensated for the losses in the previous year. Further, the insured farmers do not receive any policy documents or receipts of premium charges from the banks or insurance companies. Thus, there has been a 20-percent drop in loanee farmers in 2017 as compared to the first year (see Table 3). Few farmers now take loans or credit, harming future yield production.

- Sometimes, a farmer is insured for the wrong crop[26] or the bank may be late in paying premiums to the insurance companies, leaving the farmer in a lurch and unable to claim payments. In Rajasthan, when the SBI did not pay the premium on time, farmers had to cultivate the next season without receiving their claim payments.[27]

- Non-loanee farmer participation has been low because they might not own the required provision documents such as an Aadhaar card. While the overall non-loanee farmer enrolment rate has fallen by five percent in 2017, there has been a 3.6-times increase in the number of non-loanee farmers than loanee farmers in Maharashtra. This is because Maharashtra changed the rules of mandatory credit-linked insurance, giving one the choice to opt out of the PMFBY.[28]

- Leasing agricultural land is prohibited in Kerala and J&K, while states such as Bihar, MP, UP and Telangana have conditions on who can lease out land, which prevents many tenant farmers from buying insurance. In Haryana and Maharashtra, tenants acquire the right to purchase land after a period of time,[29] but without land-lease certificates, sharecroppers and tenant farmers cannot be part of the scheme.

- Being only a yield-protection insurance, this scheme is not holistic and fails to take into account revenue protection. Without revenue protection, farmers do not benefit from the insurance scheme since, irrespective of the harvest at the end of the season, a negative Wholesale Price Index (WPI) for primary food articles leaves farmers under-compensated. According to data from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, the WPI for primary food articles has seen several fluctuations, with a 2.1-percent increase (144.7) in July 2018 to a 1.4-percent decline in December 2018 (144.0) to a further decline of 0.2 percent (143.8) in February 2019.[30] Lower wholesale prices of food articles render farmers unable to breakeven their investment for crop production, leaving them with little income security for the next season. For instance, even if a farmer were to reach the targeted harvest, low wholesale prices will prevent the compensation of their production costs. What is missing is a revenue-protection insurance to protect farmers from a “yield and price” risk.

- Concerns regarding the ability of the state to conduct reliable CCEs must be addressed by involving village and district-level institutions and/or farmers in different stages of PMFBY implementation. There is a lack of trained professionals to handle the CCEs, and the current technology is not reliable. This has led to delays in assessment and settlement of claims, further eroding trust in the scheme.

- Insurers still face problems in reaching farmers to convey to them the benefits of insurance, due to the lack of rural infrastructure. According to the Comptroller and Auditor General of India[31] in 2017, out of 5,993 farmers surveyed, only “37% were aware of the schemes and knew the rates of premium, risk covered, claims, loss suffered, etc., and the remaining 63 percent farmers had no knowledge of insurance schemes highlighting the fact that publicity of the schemes was not adequate or effective.” Without proper information regarding credit, insurance, premium deduction, yield-loss assessment and non-payment of claims, farmers are treated as outsiders in a scheme that is meant for their welfare.

- The PMFBY guidelines contain provisions on bidding/notification of the PMFBY by states for three years, to allow the concerned insurance companies to create infrastructure and manpower in the clusters allocated to them. Thus, every cluster or IU has a specific insurance company selling insurances, with no provision for competitive pricing that could benefit farmers. The lack of competition also serves as a disincentive for insurance companies to improve or upgrade their products and pricing, and creates a monopoly over a scheme that requires competitive pricing.

Table 3: State-wise number of farmers insured under PMFBY

Financial Issues

- Many state governments have failed to pay the subsidy premiums on time, as paying these premiums eat into their budgets for the sector. This leads to insurance companies delaying or not making claim payments. In 2016, the Bihar government had to pay INR 600 crore as premium subsidy, which was one-fourth its agricultural budget of INR 2,718 crore in 2016.[32] Since this would reduce the state government’s available fund, it chose instead to dole out direct transfers and loan waivers as cheaper alternatives to win vote banks.

- In 2016–17, private insurance companies paid a compensation of INR 17,902.47 crore, and the difference between the premiums received and compensation paid was INR 6,459.64 crore.[33] In 2017–18, they paid over INR 2,000 crore less in compensation. Thus, the outgo in compensation during 2017–18 stood at just INR 15,710.25 crore. Evidently, insurance companies are piggy-backing on the banking system, as the difference increases despite a fall in the number of farmers insured. Insurance companies continue to profit, despite a decline in the number of farmers being benefitted. Moreover, approximately 80–85 percent of the premium is paid by the government, which puts a huge burden on the exchequer, leading to delays in paying premiums and, in turn, delays in the claims-benefit process. Simply increasing the funds allocated to the scheme will not help the government achieve higher enrolments and lower premiums. What is needed is a robust system of trust and investment to provide credit and insurance. Table 4 shows that the difference between gross premium and compensation paid in the Kharif season has reduced, indicating a discrepancy in the data on the disbursement of claims and the profits made by private insurance companies.

Table 4

(In INR Crore)

| Season | Farmer Premium | Gross Premium | Claims Paid |

| Kharif 2016 | 2,919 | 16,317 | 10,496 |

| Rabi 2016–17 | 1,296 | 6,027 | 5,681 |

| Kharif 2017 | 3,039 | 19,768 | 17,210 |

source: Orfonline

Link:https://www.orfonline.org/research/pradhan-mantri-fasal-bima-yojana-an-assessment-of-indias-crop-insurance-scheme-51370/